How Management Innovation Happens

Few companies understand how such innovation occurs — and how to encourage it. To foster new management ideas and techniques, companies first need to understand the four typical stages in the management innovation process.

Management innovation — that is, the implementation of new management practices, processes and structures that represent a significant departure from current norms — has over time dramatically transformed the way many functions and activities work in organizations. Many of the practices, processes and structures that we see in modern business organizations were developed during the last 150 years by the creative efforts of management innovators. Those innovators have included well-known names like Alfred P. Sloan and Frederick Taylor, as well as numerous other unheralded individuals and small groups of people who all sought to improve the internal workings of organizations by trying something new.

Consider how our ability to manage the consistency of manufacturing processes has evolved: from Ford Motor’s introduction of the moving assembly line in 1913 and Western Electric’s invention of statistical quality control in 1924, through the quality revolution begun by Toyota Motor and other Japanese companies in 1945 and on to such recent innovations as the ISO quality standards and Motorola’s Six Sigma methodology, which were both introduced in 1987.1 Similarly, the ability to keep control of a company’s finances has changed substantially over the centuries, through such innovations as discounted cash-flow analysis, capital budgeting and, more recently, activity-based costing. Even the foundation stones of the modern business organization were at some point created by inventive and farsighted individuals: Luca Pacioli popularized double-entry bookkeeping in 1494, and the limited liability company was created in 1856.2

A historical perspective is useful because it reminds us that nothing about our current ways of working is inviolable. There are management innovations under way all the time in organizations. Many fail, some work — and only a few make history. Over time, the most valuable innovations are imitated by other organizations and are diffused across entire industries and countries. Some management innovations, including Toyota Motor Corp.’s lean production system and Procter & Gamble Co.’s brand management model, gave the pioneering companies lasting competitive advantage. Others, such as Materials Requirement Planning and investment portfolio analysis, created broader- based productivity and societal benefits. Indeed, taken as a whole, the process of management innovation is probably as important to economic and social progress as technological innovation.3 Ray Stata, the former CEO of Analog Devices Inc., a semiconductor company based in Norwood, Massachusetts, argued that, “at Analog Devices, and many other U.S. companies, product and process innovation are not the main bottleneck to progress. The bottleneck is management innovation. We have to ask ourselves, as a company and a nation, are we investing enough in management innovation?”4

But despite its importance, management innovation remains poorly managed and poorly understood. Most companies have no formal process for fostering management innovation. It is typically left to occur in an ad hoc fashion, and successful management innovators frequently observe that they succeeded “despite the system,” not because of it. Moreover, academic research provides surprisingly little help. While studies of the diffusion of existing management innovations are common, there is very little literature on the origins of management innovation and the generative processes through which it first takes shape. A recent search of the Business Source Premier database yielded some 12,774 peer-reviewed articles discussing “technological innovation” but only 114 focused on “management innovation.” With only a few exceptions,5 most of those 114 articles do not provide businesses with the tools to develop or enhance their capacity for engaging in management innovation.

To address this deficiency, we embarked on a research study to understand better how management innovation happens. We first studied the histories of some famous cases of management innovation, such as Alfred P. Sloan’s introduction of the multidivisional structure at General Motors Corp.6 We then conducted case study analyses of 11 recent cases of management innovations, using a mixture of well-known and less-publicized examples and, in most cases, interviewing at least one of the individuals responsible for implementing the innovations. (See “About the Research.”) We sought to understand the stages in the management innovation process and identify the roles key individuals play in shaping and driving management innovations.

The Management Innovation Process

The research began with a simple hypothesis: that management innovation occurs in a way similar to the well-understood process for technological innovation. We expected to observe individuals pulling together ideas and resources in novel ways, championing those ideas inside their organization, building coalitions of senior executives to support their ideas and using political skills to overcome internal resistance to the innovation.7 We did, indeed, observe all those things, but there were also two important points of difference that made management innovation a distinct process in its own right.

The first was a much more significant role for external change agents than is usually seen in technological innovation. These individuals were a mix of academics, consultants, management gurus and exemployees. They often provided the initial inspiration for a management innovation, and they frequently helped to shape and legitimize the innovation as it took hold. These external agents rarely if ever actually developed the new practices per se, but they offered important inputs to both the process of experimentation and to the subsequent stage of validation. The management innovation process therefore had a highly interactive quality. It typically took place on the fringes of the organization rather than in the core, and through the relationship between managers and external change agents, who together managed to bridge the gap between concept and implementation.

The second point of difference was a more diffuse and gradual process than is typically seen in technological innovation. Most management innovations took several years to implement, and in some cases it was impossible to say with any precision when the innovation actually took place. To some degree that can also be the case with technological innovations, but the subtle nature of the process was particularly apparent in the management innovations we studied.

Why these differences? The answer lies in the fundamental distinction between what each type of innovation creates. For the most part, technological innovations are discrete knowledge assets that can be codified, since they consist of some physical process or product and can be replicated with relative ease. Management innovations, on the other hand, are more likely to be specific to the system in which they were created, which is usually a highly complex social system with many different actors and relationships. Management innovations are also relatively tacit in nature, as evidenced by the need for outside experts like consultants to implement the innovations as they diffuse across many organizations.8 As a result, management innovations are harder than technology innovations to justify prior to implementation and harder to evaluate afterward. It is therefore not surprising that the management innovation process ends up being relatively gradual and that external agents are often brought in to justify, shape and legitimize the activity.

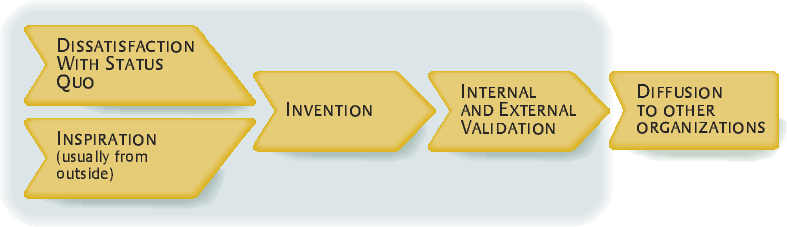

Our research revealed a management innovation model with four main stages, with different roles played by internal and external actors at each stage. (See “The Management Innovation Process.”) The four stages are, (1) dissatisfaction with the status quo, (2) inspiration from other sources, (3) invention, and (4) internal and external validation.

The Management Innovation Process

The Management Innovation Process

Management innovation typically occurs in a number of recognizable stages. The key central phase, invention, is preceded by a combination of dissatisfaction with the status quo (inside the company) and inspiration from others (typically outside the company). Invention is then followed by a process of validation both inside and outside the company.

Stage One: Dissatisfaction With the Status Quo

In the cases we studied, the internal problem that management innovation addressed was always some level of dissatisfaction with the status quo within the company. The level of dissatisfaction varied, ranging from a nagging operational problem to a strategic threat to an impending crisis.

Consider the crisis-driven end of the spectrum first. Litton Interconnection Products was a factory in Glenrothes, Scotland, engaged in the assembly of back-plane systems for computers. In 1991, George Black was brought in by the U.S. parent company to turn around the factory. As he explained, “We were a company going nowhere, doing assembly work no different from the work of dozens of larger, more efficient competitors. So we thought: ‘What should we do?’ And the answer we came up with was to be different — to provide a new service to our customers, and a new way of working. It was deliberately contrarian, and somewhat risky, but we did not have much to lose.”

Black put in place a radical new design: a business-cell structure with each cell of employees dedicated to meeting the entire needs of a single customer. Employees were trained in a broad range of skills, from manufacturing to sales to service. The net result was a dramatic improvement in customer responsiveness, reduced cycle time and much lower staff turnover.

The most common source of dissatisfaction leading to innovation is a strategic threat that has started to take shape through changes in the business environment or the emergence of new competitors. Consider the situation faced by GlaxoSmithKline PLC, the U.K. pharmaceuticals giant, in 2000. Big pharmaceutical companies like GSK were suffering from declining productivity in their research and development activities, while at the same time many biotechnology companies were becoming remarkably successful, despite having only a fraction of the resources of GSK. As Tachi Yamada, GSK’s global head of R&D, observed: “Large pharmaceutical companies are very good at the front end of drug discovery, which often involves capital-intensive screening of compounds. They are also very good at the later stages of drug development — running large clinical trials. It is in the important middle ground of this process — converting promising compounds into viable products —where the flexibility and responsiveness of smaller biotech firms is essential.”9

Yamada’s solution was a radical restructuring of GSK’s drug development operations into seven Centres of Excellence designed to have biotechlike levels of flexibility and autonomy while still benefiting from the scale of GSK’s global presence. Although the real results of this innovation will not be known for many more years, the early indicators are very promising.

A third type of dissatisfaction that can lead to innovation is the nagging operational problem. This is best exemplified by Motorola’s development of the Six Sigma methodology for controlling the quality of a manufacturing operation. This innovation can be traced back to the concept of zero defects proposed by Motorola quality manager Bill Smith in 1985 and “the Six Sigma Quality Program” that CEO Bob Galvin subsequently initiated in January 1987. But the inspiration for Smith’s idea was not a specific problem facing the company; instead, the methodology was developed as part of an ongoing drive for excellence in manufacturing quality that had been in place since Galvin became CEO in 1981. Motorola, like many Western companies at the time, was struggling to keep up with the quality levels produced by its Japanese competitors. Six Sigma was revolutionary in its consequences for Motorola and for many other companies, but it was evolutionary in its origins.

These three examples highlight the multifaceted nature of dissatisfaction. Dissatisfaction can be framed as a future threat, a current problem or a means to escape a crisis. But the important point is that management innovation is generally a response to some form of challenge facing the organization. Unlike technological innovations, which are sometimes created in a laboratory without much thought as to what problem they might solve, management innovations tend to emerge through necessity.

Stage Two: Inspiration From Other Sources

While management innovators have a desire to make their company a better place, they also need inspiration, such as examples of what has worked in other settings, analogies from different social systems or unproven but alluring new ideas. Our research did not suggest any particular patterns in the sources of new ideas, but it revealed a breadth of thinking among management innovators that allowed them to strike out on their own paths.

One source of inspiration was the ideas of management thinkers and gurus. For example, in 1987, Murray Wallace was the CEO of Wellington Insurance Co., at the time a troubled insurance company located in London, Ontario. While pondering his options for revitalizing the company, Wallace picked up Tom Peters’s new book “Thriving on Chaos.” Wallace translated Peters’s broad manifesto for radical decentralization into an operating model that became known within the company as the “Wellington Revolution.” Wallace’s model helped Wellington achieve a dramatic turnaround in growth and profitability.10

In some cases, organizations and social systems much further afield were a source of inspiration. In the early 1990s, Oticon, a hearing-aid company based in Copenhagen, Denmark, developed a radical organization model with no formal hierarchical reporting relationships, a resource allocation system built around self-organized project teams and an entirely open-plan physical layout. This new model helped Oticon achieve dramatic increases in profitability over the rest of the decade. Lars Kolind, the CEO of Oticon and the architect of these changes, got his inspiration for this organizational model from his deep involvement in the Boy Scouts of America movement. As Kolind put it, “The Scouting movement has a stronger volunteer aspect, and whenever Scouts come together, they cooperate effectively together without hierarchy. There is no game-playing, no intrigue; we are one family brought together through common goals. My experiences in Scouting led me to focus on defining a clear ‘meaning’ for Oticon employees, something beyond just making money, and to build a system that encouraged volunteerism and self-motivation.”

More generally, many of the management innovators in the study had unusual backgrounds or had worked in a wide variety of different functional areas or countries. An interesting example is Art Schneiderman, the manager at Analog Devices who in 1987 developed the prototype for what became known as the Balanced Scorecard. Schneiderman was strongly influenced by Jay Forrester’s system dynamics concepts during his MBA training at MIT’s Sloan School of Management; then, before he joined Analog Devices, he spent six years as a strategy consultant with Bain & Co., working on quality management projects in Japan. This background gave Schneiderman insight into continuous improvement techniques that were being used in Japan, plus a systemwide perspective on the functioning of the organization. So when he was asked by Analog Devices CEO Ray Stata to develop a quality improvement process for the company’s manufacturing, Schneiderman quickly developed a set of metrics that included both financial and nonfinancial components.11

While very different, the examples of Wellington, Oticon and Analog Devices all highlight a simple point: Inspiration for new management innovation is unlikely to come from within a company’s current industry. Most companies get sucked into a pattern of benchmarking and competitor-watching that leads to highly convergent practices within an industry. By gaining inspiration from other sources, the management innovators in these three companies were able to develop something radically new to their organizations.

Stage Three: Invention

In every case of management innovation we studied, we asked about the “eureka moment” when the new practice, process or structure was first dreamed up. But perhaps not surprisingly, the “eureka moment” rarely materialized. The only exception was Art Schneiderman’s invention of the Balanced Scorecard. As he described it, “I was in charge of the monthly business meetings. I would always put the nonfinancial performance measures first on the agenda, followed by the financial measures, and Jerry Fishman, my boss, would switch them around. After several of these meetings, Jerry called me into his office and said: ‘I understand your motives and you understand mine. This game we’re playing is not productive. You figure out a way to satisfy both of us, or we’ll just do it my way.’”

Faced with that challenge, Schneiderman found inspiration a few days later. While at home in the evening, he saw a television commercial that emphasized how a certain type of candy was a combination of two different products: peanut butter and chocolate. As Schneiderman recalled, “Suddenly the light bulb lit: Combine the financial and nonfinancial metrics as a single agenda item. So I added a small number of key financials at the top of the scorecard, and the problem was solved to everyone’s satisfaction.”12

Our research suggests that “eureka moments” such as that are rare in management innovation. The management innovator brings together the various elements of a problem (that is, dissatisfaction with the status quo) with the various elements of a solution (which typically involves some inspiration from outside, plus a clear understanding of the internal situation and context). However, the manner in which these elements are brought together is usually iterative and gradual, rather than sudden.

While not able to identify a “eureka moment” per se, most management innovators could point to a clear precipitating event that provided them with a focal point around which to coordinate their efforts. Consider the example of Skandia Insurance Co. Ltd., a Swedish insurance company that grew rapidly in the early 1990s through its highly successful life insurance business. During this period, Skandia, which is based in Stockholm, pioneered an approach to reporting the value of intangible assets such as human capital to external stakeholders. Leif Edvinsson was the primary architect of this management innovation, and, when interviewed, he identified the reasons why traditional accounting measures had become increasingly irrelevant. He spoke of various people who had influenced his thinking, from Dee Hock, the founder of Visa, to Bjorn Wolrath, the CEO of Skandia at that time. But the critical event, from Edvinsson’s point of view, was the moment when Wolrath gave Edvinssson the title director of intellectual capital. That act legitimized Edvinsson’s ideas and gave him a license to introduce formally Skandia’s new Navigator model for corporate performance measurement.13

Another example involving a precipitating event took place at Hewlett-Packard Co. In 1991, HP developed a global account management structure to provide services to the company’s international customers in a coordinated fashion. That is now a standard way of managing international customers, but at the time it was unheard of in the information technology sector. The key individual behind the innovation was Alan Nonnenberg, who had worked on three continents and had experience with HP’s major-account program in the United States. The defining event was that Nonnenberg was asked to lead the global account management initiative. He then worked through the design and development of the new structure by applying what he had learned from the U.S. major-account program to a global template. As Nonnenberg explained, “We thought we were being truly innovative, and we weren’t able to get any ideas from other companies’ experiences. But I basically put my head down and put the structure together and worked through obstacles as they arose.”

A small number of the innovations studied emerged through largely serendipitous circumstances. For example, Sun Microsystems Inc. created one of the first independent software developer networks while preparing for the launch of Java in 1995. But although the network proved enormously successful, within Sun there had been little conscious thought ahead of time as to how the developer community might evolve. “We had no idea of the magnitude of what we were creating,” observed George Paolini, the chief architect of the Java initiative.

Stage Four: Internal and External Validation

In one important respect, management innovation is like every other form of innovation: It involves risk and uncertain returns, and as a result it encounters resistance from people who do not understand the potential benefits or feel they will lose out as a result of the innovation. And it is impossible to predict accurately whether any innovation’s benefits will exceed its costs until the innovation has been tried. A critical stage in the process, then, is for the management innovators to generate validation for their new idea.

While validation from external parties is important, the more crucial step, at least initially, is for the innovation to gain internal acceptance. Our research confirmed many of our expectations about the process of validation inside the organization: A clear champion is needed to drive the innovation forward, a respected senior executive sponsor helps enormously to give the innovation credibility, and early victories are important because they provide evidence that the innovation is sound. Indeed, as noted earlier, management innovation is trickier to validate than technological innovation, because management innovation is less easily codified, requires the willing participation of many people to be effective and often does not deliver results until several years after implementation. The management innovator may initially be a brilliant inventor, but it is important for that inventor to then build a supportive coalition to carry the invention into the organization.

Lars Kolind’s experiences at Oticon were typical.14 Kolind’s first task was to persuade the owners of the company that a radical change was necessary to confront the challenge posed by giant competitors. He then embarked on a massive internal selling program to explain the nature of his proposed changes to employees. Inevitably, there were some employees who chose to leave because they were not comfortable with Kolind’s changes, but most were quick to see the benefits and became involved in implementing what became known as Oticon’s “spaghetti organization.”

Another distinctive feature of the management innovation process is the importance of “external validation,” which is essentially a stamp of approval from an independent observer, such as an academic, a consultancy or a media organization. Again, the reason external validation proved to be so important has to do with the uncertain and ambiguous nature of most management innovations. Lacking hard data to prove that a particular innovation was working, senior executives in companies frequently sought external validation as a means of increasing the level of internal acceptance for the innovation. This process of validation also typically increased the visibility of the innovation to competitors or companies in other industries, which tended to reinforce the innovation further. Our research identified four common sources of external validation.

The first is the business school academic, who typically acts as a thoughtful observer of the emerging management innovation and who sees his or her role as codifying the practice in question for use in research and classroom teaching. The best example of this is probably the development of activity-based costing and the Balanced Scorecard by Robert Kaplan and colleagues.15 As observed earlier, Schneiderman was the first person to put a Balanced Scorecard into practice, but Kaplan wrote a case study on Analog Devices in which Schneiderman’s “corporate scorecard” was featured, and Kaplan subsequently used the example in a Harvard Business Review article. This process, Kaplan argued, allowed Schneiderman’s innovation to become more effective: The concept “had become codified, generalized and shown to be applicable to a much larger audience than the originating company.”

A second common source of external validation is the consulting organization that sees its role primarily in terms of codifying and documenting the innovation so that it can then be used in other settings. Six Sigma was successful inside Motorola, but it only received external attention when Mikel Harry and Richard Schroeder, two Motorola executives, created a specialized consultancy operation to sell their methodology to other companies.16 Their immediate successes in Allied Signal and General Electric led to widespread acceptance of the Six Sigma concept and a rethinking of its importance inside Motorola.

The third source of external validation is media organizations, which see their role as broadcasting the story of the innovation to a wide audience. For example, GSK’s Centres of Excellence for Drug Discovery received significant media coverage when they were announced, although very few details were provided about how they would work. In another case, General Foods Corp.’s Quality of Work Life experiments in work-flow design at the company’s dog food factory in Topeka, Kansas, became nationally known following a Newsweek story about the innovations.17

Finally, external validation can also occur through industry associations. HP’s global account management structure was initially validated through HP’s involvement in IT industry forums where best practices were shared among competing companies. A classic example of a management innovation that received this type of external validation is Total Quality Control, later renamed Total Quality Management. W.E. Deming and other quality experts gave a series of lectures before the Japanese Union of Scientists and Engineers in the early 1950s. Various member companies of that union then started taking up TQM and sharing their experiences.

These four sources of external validation are not mutually exclusive, and some of the more widely known management innovations receive validation from multiple sources. The important point, though, is that external validation has a dual role. It increases the likelihood that other companies will attempt to adopt the innovation in question, but it also increases the likelihood that the pioneer company will stick with the innovation. For example, we asked Schneiderman what might have happened to his “corporate scorecard” if he had never met Robert Kaplan, and he acknowledged that the innovation might have completely withered and died inside Analog Devices.

There are probably many management innovations that never receive much attention from outside the organization. Some of these innovations may be successful in their own right, but they often remain unnamed and unrecognized even internally for the benefits they provide. Other innovations may offer great promise but atrophy after the innovator moves on to other challenges.

Accelerating the Process of Management Innovation

What can managers do to improve their company’s capacity for management innovation? While our research suggests that companies have traditionally pursued management innovation in an ad hoc manner, the process could be made more systematic. Six common themes emerged from the research that should serve as useful pointers for a company that would like to direct its management innovation efforts more seriously.

Become a conscious management innovator.

Most companies set up some sort of innovation function to meet the need for product and service innovation, whether in the form of a physical R&D lab or the assignment of a clear mandate for that type of innovation to an individual in the organization. But how many businesses have similar levels of awareness and dedicated structures in place to foster management innovation? Selling the importance of management innovation to the organization is a crucial first step toward becoming a management innovator.

Create a questioning, problem-solving culture.

When employees are faced with an unusual problem or challenge in the company, what is their typical reaction? Do they look the other way? Do they resort to a standard solution that has already been endorsed by competitors? Or do they look deeper into the problem, see the problem in new ways and start to hypothesize about new ways of solving it? Only the latter path can lead the company toward management innovation, so encourage employees to examine the unexplored and avoid easy answers.

Seek analogies and exemplars from different environments.

If the problem a company faces is one of increasing its resilience, it could make sense to try to learn from highly resilient social systems, such as parliamentary democracies, cities or faith systems.18 If the problem is one of increasing the motivation of employees, then look at the Scouting movement, open source software or any number of other voluntary organizations. Exposing employees to many different types of environments and different countries of operation is also invaluable as a means of opening up their minds to new alternatives.

Build a capacity for low-risk experimentation.

In one company we have been working with, there is a sustained effort under way to encourage individuals and teams to come up with management innovations to tackle everyday problems with the existing bureaucracy and processes. But to make this initiative work, the company’s leaders realized they could not allow all the new ideas to go “live” in the entire organization. So they opted for an experimental model, in which each innovation could be tested with a limited number of people and for a limited period of time. That has ensured that ideas get a chance to be implemented, without crippling the functioning of the whole organization.

Make use of external change agents to explore your new ideas.

While companies can and should manage the innovation process themselves, there is value in selectively making use of outsiders such as academics, consultants, media organizations and management gurus. They fulfill three primary roles: They represent a source of new ideas and analogies from different settings, they can act as a sounding board for making sense of a company’s emerging innovations and they can help to validate what is accomplished.

Become a serial management innovator.

The real success stories in management innovation are not the companies that have innovated once or twice. Instead, it is the companies with multiple successes — the serial management innovators. GE is a serial innovator, famous not just for management innovations such as Work-Out and Boundarylessness but also much older innovations such as strategic planning, executive development and the commercialization of R&D.

Management innovation is ingrained in the GE culture as a key driver of the company’s competitiveness. Toyota is also a serial management innovator. It has continuously added elements to its lean production system, such as just in time, kanban, target costing and parallel sourcing. Each of these elements strengthened the existing lean production system and reinforced Toyota’s long-lasting competitive advantage.

These six points are certainly not some kind of formula for management innovation. The process of developing radical new ways of working will always have some dose of luck and randomness to it. However, managers can certainly tilt the odds in their companies’ favor by keeping these ideas in mind.

History shows that management innovation has been a key driver for competitive advantage for many companies. For companies that invest in a capacity for pursuing management innovation systematically, the potential returns can be rather substantial.

References (18)

1. J. Folaron, “The Evolution of Six Sigma,” Six Sigma Forum Magazine, August 2003, 38–44.

2. J. Micklethwait and A. Wooldridge, “The Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea” (New York: Random House, 2003).

Comments (2)

Travis Barker, MPA GCPM

tsmith